Brief Context

I want to begin by contextualizing the “in-surgence”of the sp’ijilal O’tan, a Tseltal Maya concept that could be translated as “knowledges or epistemologies of the heart.” It is extremely important for me to situate the emergence and “in-surgence” of the term in a complex context within the sociocultural, political, and epistemological struggle of our expansive present. Tseltal Mayan language and culture are found in Southern Mexico, in the highlands and jungles of the state of Chiapas. I come from this accomplished civilization, whose language—part of the Mayan language family—is spoken daily by more than 400,000 people in the region.

The In-surgence of Sp’ijilal O’tan

The reflection and “in-surgence” of sp’ijilal O’tan, or knowledges or epistemologies of the heart, within academic contexts, began when we started to think and rethink our place in the cosmos. In this process, we realized that we had forgotten a cosmos, that our heart was displaced and misplaced, and that we had to “make our heart return” to this forgotten cosmos.

A first stage of making the heart return to the forgotten cosmos began in the early 1990s, when I decided to abandon a path that was leading me to what I called “spiritual colonization.” During that same decade, and more specifically in 1994, the Zapatista movement erupted under the slogan “Never Again a Mexico Without Us,” posing the political-epistemological challenge of constructing “a world that can hold many worlds… that can hold all peoples and their languages.”

These historical events led me to “in-think” (in-pensar) Tseltal Maya life, and to recognize the ways we weave our thoughts. This type of reflection then led me to a larger discovery, which we as a people have internalized over several centuries. I am referring to our condition as colonized subjects and peoples since the Conquest; our thoughts are at once negated and instrumentalized. I have called this imposed historical condition a “process of domestication”; “de-domestication” is a permanent antinomy in our communities.

The act of thinking and rethinking our place in the world and the cosmos has led us, since the 1990s, to situate our heart. We began to in-think, that is, to think and reflect from within, using our own Tseltal Mayan terms. Naturally, the “in-surgence” of Tseltal terms was not an easy reflection. The reason for this was, and continues to be, the historical and epistemological process of colonization we have endured as a people.

From the Mechanisms of Forgetting and Displacement of the Heart

From Forgetting to the Acts of ‘Making the Heart Return.’ In 1992, I realized we had forgotten the cosmos after someone shook my being and my consciousness with a single phrase: “pinche indio” (goddamn Indian). I already knew the term “Indian” had negative and derogatory connotations. As we know, since the Conquest and the colonial period, the term “Indian” has been a political category used to insult and exterminate the “others.” The “others” were and are the people who lived on this land before colonization. Many of the people of the past are the people of today.

On October 12, 1992—while a mestizo person was calling me a “goddamn Indian”—thousands of Maya peasant women and men were marching in the city of San Cristóbal de Las Casas to protest the 500th anniversary of the Spanish invasion of our ancestral lands.When the crowd arrived at the statue of Spanish captain Diego de Mazariegos, conqueror and founder of San Cristóbal de Las Casas, a group tore down the statue of the colonizer. The statue stood in front of the monumental Catholic church of Santo Domingo, which had been run by Dominican friars since the colonial period. Both the statue of Diego Mazariegos and the church represent an affront to our history as a people. What exactly was stirring at the core of our heart? Something was emerging in both our individual and our collective heart.

Our imposed historical condition. From the moment our lands were conquered, our people’s life-worlds split in two, and there were religious, political, judicial, linguistic, and epistemological ruptures in our worldview. Through the Enconmiendas, a form of slavery that exploited indigenous labor, the colonizers evangelized and transmitted European rules and customs.

They imposed their Judeo-Christian religion, banning the spiritual practices of the conquered peoples—although some elements clandestinely survived. They established a system of government, along with a new social order, dictated by imperial law. Our systems of economic exchange were transformed. Spanish was imposed as the official language of Mexico, and it remained so until 2003, when the native languages that survived the long process of linguistic extermination acquired a “constitutional standing,” which is only valid at the local and regional levels.In the epistemic arena, our sources of knowledge and history were burned and destroyed. The codices we know today survived only because they had been stolen by colonizers. They characterized our knowledge as superstition. They even questioned if native people were endowed with reason and souls. Across the Americas, native communities suffered the same fate, except for those who allied themselves with the invaders.

The colonizer’s supremacy was imposed through destruction and subjection, as Fray Bartolomé de Las Casas wrote in A Short Account of the Destruction of the Indies. In this emblematic work, he shows how the colonizers carried out a systematic extermination.

Both the socio-historical context mentioned above in broad strokes, as well as our individual and collective experience, have been our starting point. They have led us to the avatars of scrutiny of our collective being. It was devastating to realize that the indigenous spirit “was defeated and subjugated” only by the power of the colonizers’ weapons, given that the “meeting of two worlds”—as the Mexican educational system taught us to celebrate on October 12, Día de la Raza—was a brutal clash between two or many worlds with totally different imaginaries and ways of knowing, in a total asymmetry between civilizations. We understood that much of what we are today as collective subjects had been a socio-historical imposition by hegemonic colonial power. Their leaders and soldiers domesticated our bodies and spirits through the force of whips and swords, while the clergy used persuasion to “peacefully” colonize our hearts and minds. If we are a domesticated people, is “de-domestication” possible? What would that be like, and how do we do it? We needed to immerse ourselves in the “deep Mexico,” as Guillermo Bonfil Batalla called the Mexico of our native people, with its own civilization, its “other” imaginaries, and its own systems of thought. These have—we have—always been here, although the “Other,” in this case the Mexican State, has considered us a problem to be defeated on all fronts: cultural, linguistic, political, economic, judicial, and epistemic-educational.

From Discouragement to the In-surgence of Ch’ulel

“Goddamn Indian” shook me to my core. It was a verbal insult that made me arrive at, or awaken to, my own consciousness. This expression is used by Spanish speakers throughout the Americas, so I can assert that we indigenous people have, as a whole, been labeled “goddamn Indians.” Despite the fact that abuse and contempt crush our spirit, those situations often bring us to consciousness and “make our heart return” to the forgotten cosmos. In Tseltal Mayan we call this return: xjul xch’ulel.

The colonial invasion imposed a new reality and new imaginaries for indigenous peoples of Mexico—and for pre-Hispanic peoples throughout the Americas—and our life-worlds suffered a rupture in everyday existence and in their very being. By attending the various rituals of different Maya communities in Chiapas, I reaffirmed my grandparents’ teaching-learning, and I can now attest to the fact that the Mapuches, the Aymaras, as well as indigenous peoples from North America, all share a similar concept: the existence of ch’ulel in every living being. They would therefore have to be given ich’el ta muk’ (respect) for a lekil kuxlejal (a plentiful, dignified and just life). In the following section, I outline some definitions of ch’ulel to better understand it.

Definitions of Chu’lel

The first definition of ch’ulel has to do with the primary essence of existence; we could also call it vital power or energy. Both human and non-human beings have ch’ulel, which means that all existing beings have ch’ulel. This notion of life exceeds Western or scientific classifications, which is based on the existence of animate and inanimate beings. In the Tseltal Maya understanding of life, human beings, as well as plants, animals, minerals, water, oxygen, and other existing elements all have ch’ulel. It is ch’ulel that makes us interact in the vast field of nature and existence. From the micro to the macro, we interact and mutually affect each other. Ch’ulel is what places us in the cosmos among other beings.

Second definition. We also refer to the process of language acquisition by infants, when they begin naming the things that surround them, as xjul xch’ulel. There is a slight variation in ch’ulel: The “x” before ch’ulel indicates that it refers to a third person. Ch’ulel is still recognized in people who do not acquire or develop spoken language skills.

Third definition. We also use the term to refer to a type of consciousness or a notion of reality. When a person’s conscience is in an altered state due to substances, for example, we say ch’ayem xch’ulel, meaning they have lost their ch’ulel, they’re not in possession of the five traditionally known senses. We could also say ch’ayem yo’tan, meaning that their heart is lost. But it could also be a distraction by which a person isn’t fully themselves. When the person returns to normal, we say julix Xch’ulel or kuxix Yo’tan, meaning that their ch’ulel has returned, or their heart has been revived.

Fourth definition.This definition of ch’ulel has a social or collective character, that is, a socio-communal ch’ulel. It includes family, community, and other spaces of social interaction. Family and community spaces have existing life practices. So this type of ch’ulel is a historical construct, a part of our collective memory, the accumulation of knowledge that is transmitted and recreated from generation to generation. As historical memory, it includes a consciousness of the pain caused by past and present injustices. When collective subjects want to transform the socio-historical conditions that have brought them to their current condition, an insurgent ch’ulel emerges—as we saw in 1994 with the Zapatista uprising. All these experiences live and are cultivated in the O’tan-heart and thus become sp’ijilal O’tan. They become ways of thinking, acting, and being in the world. Sometimes they are our own, sometimes they are adopted and imposed, but they all are changeable.

Sp’ijilal O’tan: Knowledges or Epistemologies of the Heart

One of the ancestral teachings of Tseltal Maya elders is that everything in existence must be given ich’el ta muk’ because everything has ch’ulel. If they are not treated with ich’el ta muk’, “ya x-ok’ yo’tan sok ya x-ok’ xch’ulel,” as we say in Tseltal. That is, their heart and ch’ulel weep.

As we can see in the paragraph above, beyond ch’ulel, another element is incorporated: O’tan. This appears when we say we have to give ich’el ta muk’ to everything in existence, as previously mentioned in the third definition of ch’ulel. As already noted, the literal translation of O’tan is heart. We could think that when we mention the O’tan-heart, we are talking about an organ, or the physical, material body, and that ch’ulel is a spirit, an immaterial metaphysical entity. But when we talk about O’tan-heart we do not mean the organ. It is a metaphor, an image or space, a being or entity that feels and thinks. It could be the subject itself, as can be seen in this everyday dialogue between Tseltal people, which I cited in a 2011 article:

Bixi awo’tan (What does your heart say?), Lekbal ay awo’tan (Is your heart well?), Mame xa mel awo’tan (May your heart not be sad), Ma xch’ayat ta ko’tan (I do not lose you in my heart or I do not forget you), Kuxix ko’tan (My heart rested or resuscitated), Tse’el ko’tan yu’un ya kilbet asit (My heart laughs because I see your eyes), K’uxat ta ko’tan (You hurt in my heart or I love you), Yutsil ko’tantik (The kindness of our heart), Ya jnop ta ko’tantik (We think or meditate with and in our heart), A’yantaya ta awo’tan (Discuss it in your heart), Nopa sok ajaol awo’tan (Think with your mind and heart) (López Intzín 2011).

I just want to clarify in the above quote that O’tan appears in different possessive forms: awo’tan (your heart), ko’tan (my heart), and ko’tantik (our heart). So we can find other expressions with possessive forms for third person singular and plural. The O’tan element never varies. From a linguistic perspective, O’tan appears as a noun. It is not always so; in particular expressions it implies or indicates action (doing something), for example: ya ko’tanin snopel jun, teantse ya yo’tantay sna yawil, or ya yo’tanin slumalik te jme’tik jtatike. These idiomatic Tseltal expressions allude to having to do things with heart and surrendering ourselves with heart; in other words, we have to completely dedicate, concentrate, and surrender ourselves with heart when carrying out an act or action in time and space. We have to carry out the act of yo’taninel spasel-smeltsanel (“enhearting” the process of doing-constructing), as I cite in the same 2011 article:

[…] Everything is “enhearted” (Todo se corazona). The acts of thinking – yo’taninel snopel – and doing are enhearted – yo’taninel spasel-smeltsanel. And just as thinking and knowing are enhearted, it is also said that knowledge and understanding are felt by what we think-feel or feel-think with the heart… If we enheart feeling-thinking and feeling-knowing, it makes us different from “Others.” We belong to another ts’umbalil (culture), and are perhaps so different in our construction, naming, and relationship with the cosmos-world… that we use both heart and mind, love and reason, leading us to knowledge-p‘ijilal… In this way, the coupling of heart and mind—love, passion, and reason—more than a disputed dichotomy is a complementary notion that shapes Tseltal Maya rationality. We feel in order to think and we think in order to feel, so that any creative act passes through reason, and any rationality travels through our heart and feelings.

With regard to the above, the O’tan-heart becomes a space and center in the in-corporation of people’s everyday life experiences and the source of our culturally situated knowledges.

Fields of Cultural Knowledges

Sp’ijilal O’tan does not simply name what we know from experiences accumulated throughout history. It also refers to a constellation of practices, concrete modes of community life—ways of being in and with the cosmos. They imply rationality from ich’el ta muk’, recognizing the greatness and dignity of all that exists. It is the art of knowing and recognizing oneself in “otherness,” and the art of survival by creating different systems and fields for caring for life. Listed below are the systems we believe to be comprised in sp’ijilal O’tan.

- Systems of care and healing that include: midwifery, herbalist medicine, healing through prayer, ritual chants, development of various instruments and their use for different purposes, healing chants. Diagnosis and treatment of different illnesses and their treatments.

- Dreams.

- The care and preservation of seeds and different food crops.

- Ritual cycles for the care of water, sown land, forests, etc.

- Systems for numbering and counting time.

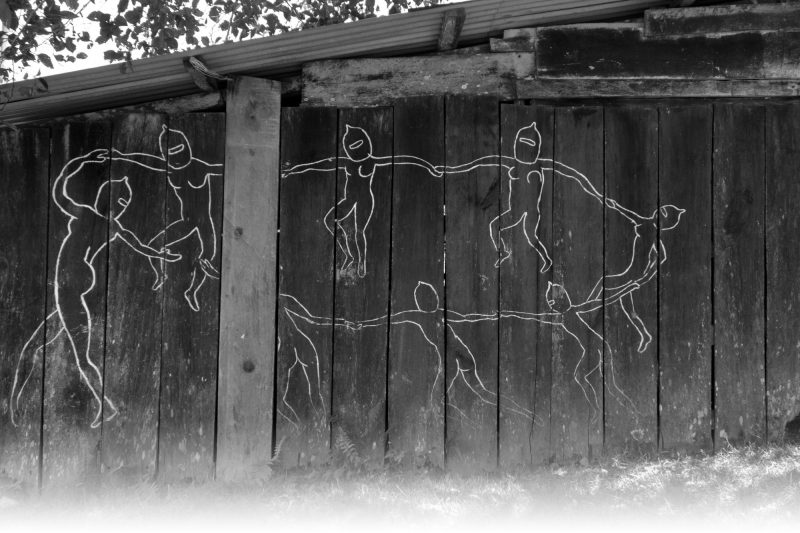

- Pre-conquest and contemporary designs representing the cosmos in textiles and pottery.

- Recognition of the lunar cycle for such activities such as planting crops and cutting down trees.

- The art of resistance and “joyous rebellion.”

These are just some fields or systems included in sp’ijilal O’tan. There are more, however, and one of them—the notion of “being well”—is ethical in nature, and relates to good external behavior, to ich’el ta muk’ (the recognition and respect for the greatness of existence), and to lekil kuxlejal (a plentiful, just, and dignified life).

Below, I broadly outline the art of resistance and “joyous rebellion,” or what I have called “Political epistemology of the heart and the Zapatista Caracoles.”

As we know, in 1994 the Maya were part of the indigenous movement known as the Zapatista Army of National Liberation (EZLN, by its acronym in Spanish), which broke through the veil of forgetting, injustice, negation, and contempt that has lasted 500 years. They established centers of political operations first called Aguascalientes and later renamed, in August 2003, Zapatista Caracoles (snails). When announcing the transformation of Aguascalientes into Caracoles, the EZLN issued this statement:

[…] They say it is said that they used to say that the caracol represents the journey into the heart, which is what the ancestors called knowledge. And they say it is said that they used to say that the caracol also represents the journey out of the heart and into the world, which is what the ancestors called life. And not only that, they say it is said that they used to say that would summon the collective using the caracol, so that words were relayed from one person to another to arrive at an agreement. And they also say it is said that they used to say that the caracol helped the ear hear even the most distant words. That is what they say it is said that they used to say […] (Subcomandante Marcos 2003, 2).

As the quote points out, the EZLN’s decision to rename their political centers was a way of reclaiming heritage; their collective gaze turned to what is properly Maya and indigenous, symbolized by the snail and its relationship to history, the heart, and knowledge. Therefore, in confronting the world, Caracoles have a political-epistemological turn; now they are houses or spaces for encounters and dialogue, bridges that connect worlds through recognition and respect:

[…] So the “Caracoles” will be like doors to enter communities, and for communities to exit; like windows to see within ourselves and to look outside; like speakers to carry our words far and to hear those who are far. But most of all, to remember that we should be vigilant and alert to the fullness of the worlds that populate the world (12).

This announcement speaks of the purposes of the Zapatista Caracoles, of their origins, but also of the Zapatistas’ way of being—that they are rebellious, disobedient, and that:

[…] When they are expected to speak, they are silent. When they are expected to be silent, they speak. When they are expected to lead, they stand back. When they are expected to stay back, they take off in a different direction. When they are expected to speak only of themselves, they start speaking of other things. When they are expected to conform to their geography, they walk through the world and its struggles (1).

So they’re not making anyone happy. And it seems they don’t care about much of anything. What they do care about is making their own heart happy, and so they follow the paths of their heart… (2).

The paths of the Zapatista O’tan have been very “other.” They are new knowledges or epistemologies of the heart, with an insurgent ch’ulel. In recent times, they have dialogued and “epistemologized” with people in the hard sciences, bringing them together to issue a challenge: celebrating the two consciousnesses. The Zapatistas have done so much since their emergence; they have gathered many different groups and sectors, both from Mexican society and from other parts of the planet, to construct other paradigms against what has been called the capitalist hydra. Sometimes they are teachers, and other times they are students obeying what their O’tan tells them. The O’tan has been the source of ways of knowing that have built new life-horizons—a political struggle from the joyous rebellion and the art of resistance.

By Way of Conclusion

To understand the presence and meaning of O’tan in our thinking and our worldview (our view of the cosmos), we must immerse ourselves in our history, understanding our origins as Maya people. In this extensive present, our reflections about sp’ijilal O’tan have led us to the act of “making our heart return” to our remote past, to our forgotten cosmos. In order for us to understand our thinking, we must understand how our knowledge-recognition, as well as the series of past and present life experiences, have led us to name it sp’ijilal O’tan. Besides paying attention to everyday speech and specific life practices, it has been necessary to read and reread different versions of the Popol Wuj. Although the text only captures the worldview, thinking, philosophy, myths and history of the K’iche’ people of Guatemala, I can state that Maya culture is a canvas in which we can find different fragments of the stories in the Popol Vuh. This book undoubtedly captures the foundational thinking of an entire civilization.

It appears that our O’tan-heart was there from the beginning. We can notice this in the first chapter, after Gukumats’ is surprised by the creation and expresses gratitude by saying: “It is good that you have come, Heart of Sky—you, Huracan, and you as well, Youngest Thunderbolt and Sudden Thunderbolt” (Popol Vuh, 60). The text then continues:

For thus was the creation of the earth, created then by Heart of Sky and Heart of Earth, as they are called. They were the first to conceive it. The sky was set apart. The earth also was set apart within the waters (60-61).

If we consider the Popol Vuh a foundational text of our thought as Maya civilization, we realize that O’tan-heart is there from the beginning as an energy that creates and pro-creates in “common-unity” (comun-unidad) between the sky and the Earth, dialoguing and “enhearting.”

Sp’ijilal O’tan, knowledges or epistemologies of the heart, invites us to “enheart” ourselves and the world, to recognize and respect the vast existence that is increasingly threatened by arrogant and indolent rationality. What unites and identifies all beings that form part of this vast existence is our ch’ulel and O’tan, and our mutual giving of ich’el ta muk’. It is a way to structure and organize the world, a way to know and understand the cosmos. More than likely, it is a way to objectivize subjective life since primordial times when the Heart of the Earth and the Heart of the Sky started dancing in order to procreate subjects with joyous rebellion.

Can humanity, the world, and all existing and living beings continue to live according to instrumentalized hegemonic knowledge, or bonded to the alienating capitalism that the Zapatistas have called the “capitalist hydra,” which keeps us subdued? Evidently not. It is urgent that we recognize and value other ways of being in the world.

One of the principles sustained by sp’ijilal O’tan, knowledges or epistemologies of the heart, is the apprehension of the world and comprehension of the cosmos. That is, an apprehension and comprehension of Life in its totality that in Tseltal Mayan is called sna’el k’inal (ya sna’ k’inal, ma sna’ k’inal). I do not want to say that such an understanding is broader or more encompassing than all others, or that it has an equivalent in the Western world; it is simply another. It has been here but has been negated and manipulated by hegemonic knowledge. So what I have presented here is a type of archeological action that discovers what has always been there. We just have to let ourselves be surprised and re-enchanted by everything that hegemonic knowledge and the capitalist hydra have disenchanted, everything in this vast existence that has been reduced to mere objects and commodities.

Works Cited

López Intzín, Juan. 2011. Ich’el ta muk’: la trama en la construcción del Lekil kuxlejal. Hacia una visibilización de saberes “otros” desde la matricialidad del sentipensar-sentisaber tseltal. Self-published.

Subcomandante Marcos. 2003. Chiapas: La Treceava Estela. Comunicados De La Muerte De Los “aguascalientes” Y El Nacimiento De Los “caracoles” Zapatistas, EZLN. México.

Popol Vuh: The Sacred Book of the Quiché Maya People. 2007. Translated and Commentary by Allen J. Christenson. Mesoweb. https://www.mesoweb.com/publications/Christenson/PopolVuh.pdf.