In the early 1970s, the band Los Alacranes Mojados (The Wetback Scorpions), led by Ramón “Chunky” Sánchez, released a ballad entitled “Chicano Park Samba.” The song narrates the founding of Chicano Park in the Barrio Logan area of San Diego in 1970. It begins with a voiceover:

In the year 1970, in the city of San Diego

Under the Coronado Bridge lied a little piece of land,

A piece of land that the community of Logan Heights

Wanted to make into a park.

A park where all the chavalitos could come and play in

So they wouldn’t have to play in the street anymore

And get run over by a car.

A park where all the viejitos could come

And just sit down and watch the sun go down in the tarde.

A park where all the familias could come

And just get together on a Sunday afternoon

And celebrate the spirit of life itself.

But the city of San Diego said,

“Chale. We’re going to make a highway patrol substation here, man.”

So on April the 22nd, 1970,

La raza of Logan Heights and other Chicano communities of San Diego got together,

And they organized,

And they walked on the land,

And they took it over with their picks and their shovels,

And they began to build their park.

And today, that little piece of land under the Coronado Bridge

Is known to everybody as Chicano Park.

¡Órale!

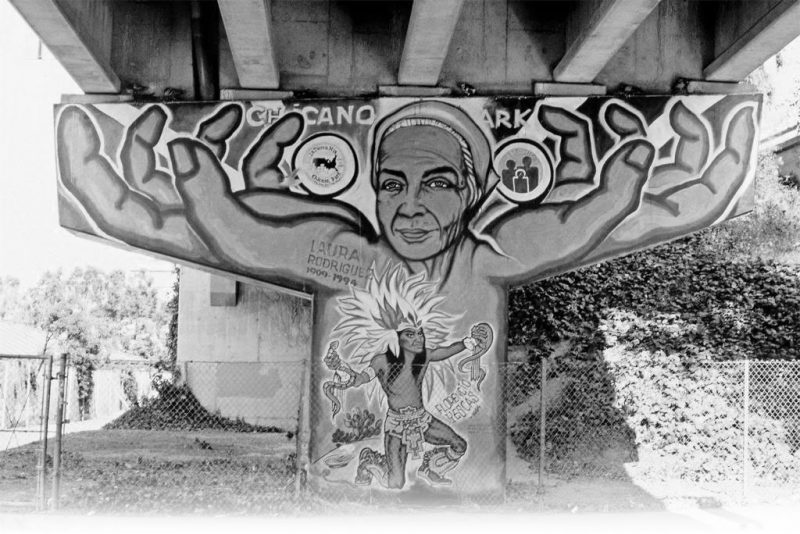

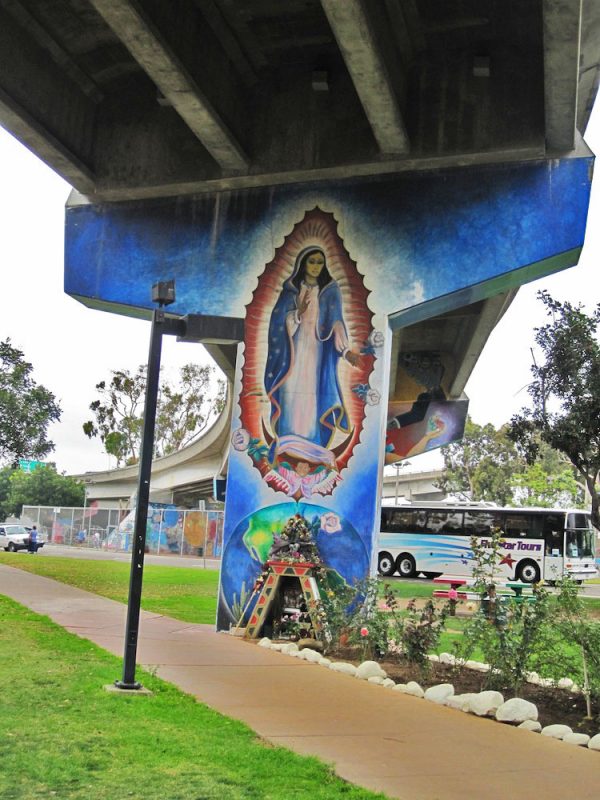

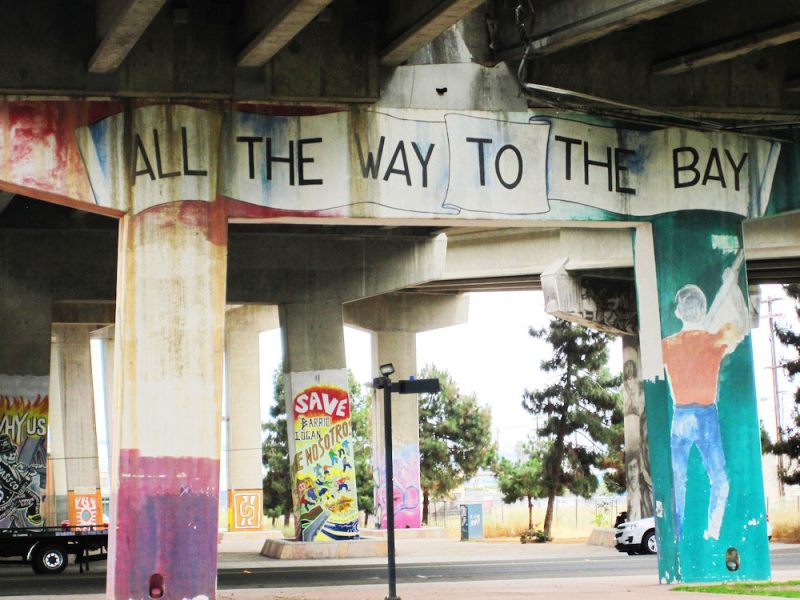

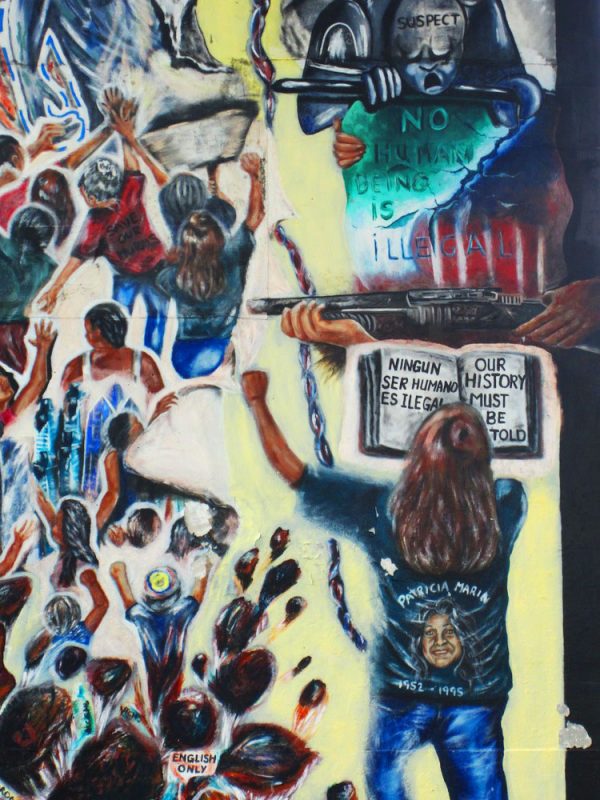

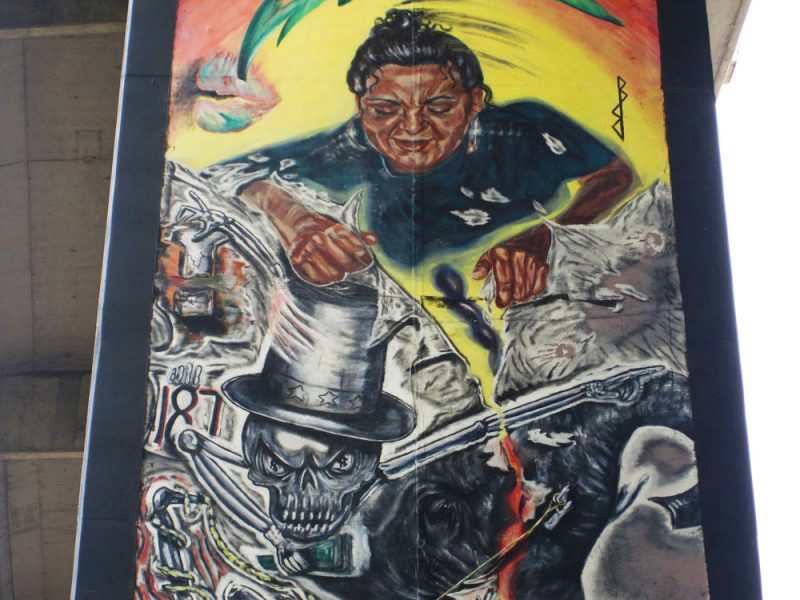

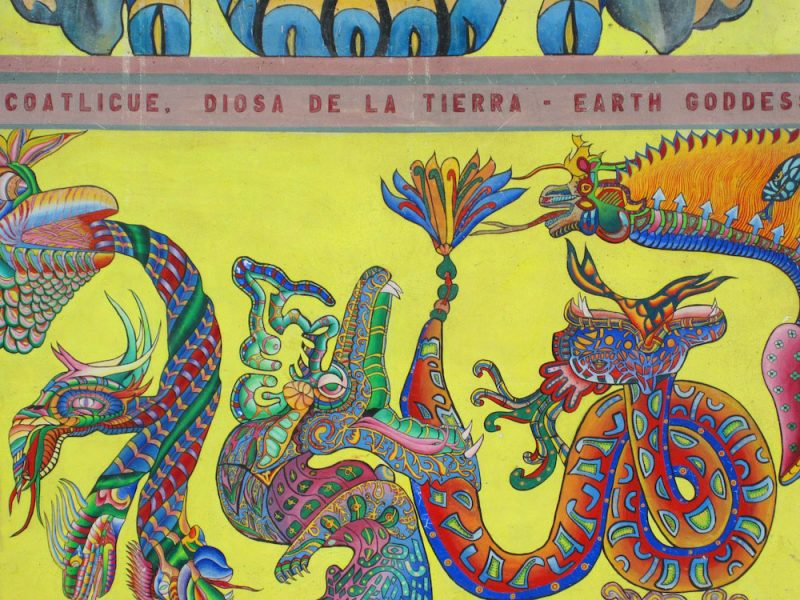

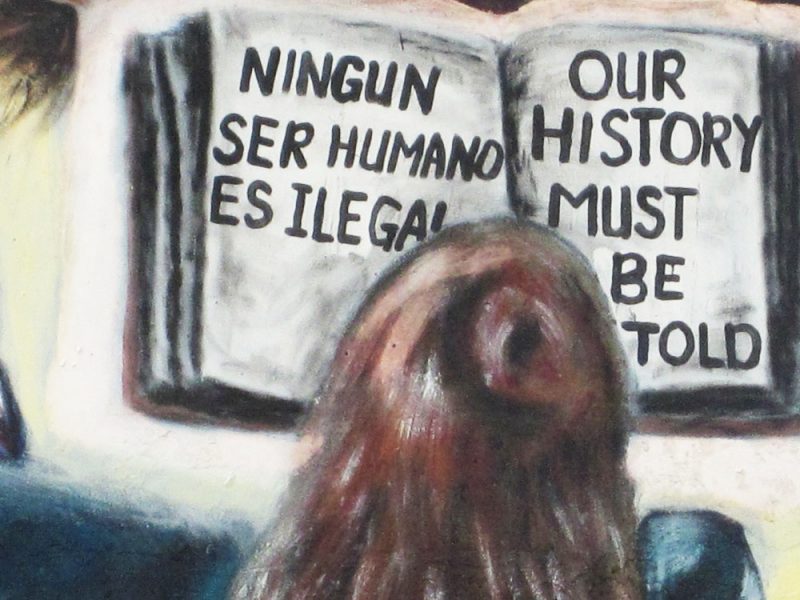

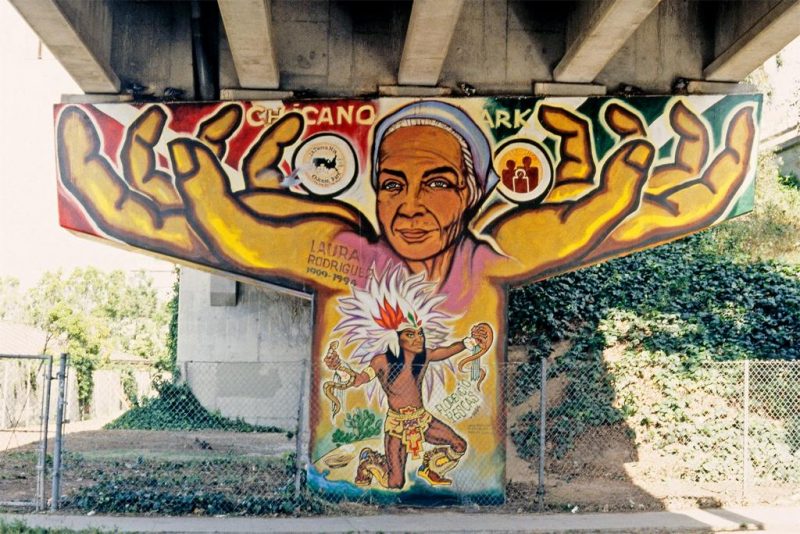

As Sánchez intones, that little piece of reclaimed land under the Coronado Bridge became a vibrant community park, as well as the home of the largest collection of Chicano murals in the United States. Artists from the San Diego neighborhood and from across the state came to paint the concrete supports and pylons that hold up the bridge and the cement barriers and abutments of the freeway’s on and off ramps. They painted every available surface, transforming the barren highway-industrial wasteland into a kaleidoscopic history lesson and vibrant public space. The murals quote from multiple sources, incorporating Maya and Aztec iconography alongside portraits and visual references to the Mexican artists Frida Kahlo, Diego Rivera, David Alfaro Siqueiros, and José Clemente Orozco; they sketch historical vignettes from Cortez’s conquest of Tenochtitlan to Cesar Chávez’s mobilization of the United Farm Workers; they depict scenes of resistance across the Americas, from the Navajo and the Inca to Che Guevara and Augusto César Sandino, all within the context of present day Southern California.

Today there are over 100 murals at the site, all of which are listed on both the California and the National Register of Historic Places. The space is regularly used for community celebrations: weddings, birthday parties, meetings, and picnics—for viejitos, chavalitos, and their familias—and also serves as a place to “just sit down and watch the sun go down in the tarde.” Moreover, the site continues to inspire artists and activists, as witnessed by the many short videos of the park that currently circulate on YouTube and Vimeo. Many of these films, often shot with flip cameras and cell phones, are set to “Chicano Park Samba” and attempt to capture the scope of the park and its murals within the context of rebellion that marks the history of the neighborhood. Much like the murals, these videos continue to make claims on the space both physically and virtually, disseminate distinctly political messages through performed and still images, and link the early history of the area to a larger narrative of confrontation and renewal across its long and contested lifespan.

In 1905, the area known as Logan Heights was annexed to the City of San Diego. One of the oldest Mexican-American communities in the state, its population grew steadily from 1910 to 1920, following the Mexican Revolution. Largely residential, the area provided low-cost housing for its residents and a source of labor for the nearby fisheries, railroads, and lumber businesses. It was a close-knit community and an easy walk to the beach, marked by a mix of Mexican restaurants, grocery stores, barbershops and other small businesses. Following World War I, however, Barrio Logan faced a number of challenges. The deportation of Mexican nationals in the 1930s and 1940s led to a decrease in population. The creation of the San Diego Naval Base cut residents off from the beach, and rezoning policies after the World War II, which transformed many residential buildings to “mixed-use,” allowed “the influx into the community of auto junk yards and wrecking operations and other light industrial plants.” According to Martin Rosen and James Fisher, who are historians of the neighborhood, “the cumulative effect of these land use policies resulted in the dislocation of families, business closures, and the construction of transportation facilities” (Rosen and Fisher 2001, 93).

The construction of Interstate 5 in the early 1960s and the erection of the San Diego-Coronado Bridge from 1967 to 1969 further divided the community, at least spatially. Nevertheless, the neighborhood maintained a close-knit and vibrant Mexican-American culture. These qualities became clear on 20 August 1970, when construction crews began clearing the land under the bridge. Residents who had been lobbying for the creation of a public park in the area assumed that they had been granted their wish. When Mario Solís, a student at San Diego City College and a member of the Brown Berets (a Chicano activist group), learned that the city was clearing the land for a California Highway Patrol substation instead of the promised park, he began going door-to-door spreading this news, like a modern-day Paul Revere (Anguiano n.d.). According to local resident José Gómez:

Tempers began to get hot. Some of the workmen were laughing at us. People who were picketing were yelling back at the workmen. Then at noon, students walked out of the schools…. They formed a car caravan down Logan Avenue to join us. The supervisor of the workmen called his men off the job and they left. When we saw that, everyone went home and got shovels and picks and rakes and we moved the land. People said, “Let’s build our own park.” That was 1pm. April 22nd (Cockcroft 1984, 82).

From the start, there was a sense of community ownership of the space. Over 300 residents and artists participated in transforming the site from a dumping ground to a functioning park filled with native plants and colorful murals. Artist Victor Ochoa recalls:

What I still remember is that there were bulldozers out there…. And women and children making human chains around the bulldozers and they stopped the construction work. They actually took over those bulldozers to flatten out the ground, and they started planting nopales and magueys and flowers. And there was a telephone pole there, where the Chicano flag was raised (Anguiano n.d.).

Everyone was involved. According to Eva Cockcroft, “People too old to work at clearing and planting cooked and brought food, tools, and plants” (1984, 84). The building of Chicano Park was both a labor of love and an exercise in creative land use. As Abran Quevedo explained in an interview with Cockcroft, “They sent this freeway down into the heart of our community and nearly killed it. We did not want it. We hated the bridge. But now that we have them, we have to deal with them creatively… The area is cement so the pillars are our trees” (Cockroft 1984, 84).

The site continues to be a contested space. In 2018, the white-supremacists group Patriot Fire targeted Chicano Park for their “Patriot Picnics.” In retaliation for the destruction of Confederate monuments across the country, the group suggested vandalizing the murals and statuary in the park. But, once again, the community of Barrio Logan mobilized in defense of the space. The group, Union del Barrio wrote:

There was some doubt that the Trumpista hate groups would show up at all …but they indeed showed up. Not only did the original San Diego based haters try to make their way into the park, but also people linked to Southern California ‘Proud Boys’ and other white nationalist organizations. When these provocateurs tried to force their way into the park they were overwhelmed by Raza on all sides and they had to be escorted out.

This narrative of community investment and land reclamation fits squarely within the ideals of the Chicano Rights Movement. Among other things, those involved in this movement challenged the legality of the 1848 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, which transferred ownership of much of what is now Texas, Colorado, New Mexico, and Southern California from Mexico to the United States. According to the Chicano Park Steering Committee website:

By taking Chicano Park, the “myth” of Aztlán metamorphosed to reality. Aztlán – the southwestern United States – was the ancestral land of the Aztecs. These ancient people migrated to the Valley of Mexico and founded an empire whose capital was Tenochtitlan, now Mexico City. By claiming Chicano Park, the descendants of the Aztecs, the Chicano Mexicano people, begin a project of historical reclamation. We have returned to Aztlán – our home (Anguiano n.d.).

By equating Chicano Park with Aztlán, park organizers forge a direct link between pre-conquest Mexican civilizations and the present day; they literally concretize the abstract utopian space of Aztlán, which novelist and poet Rudolfo Anaya has called a “homeland without boundaries,” and locate it as a very real place in contemporary San Diego (1989). Turning cement pillars into trees, they magically transform the space to fit their needs and their desires. In doing so, they enact what Edward Soja, following Henri Lefebvre, has called “Thirdspace” as a critical strategy of resistance. For Soja, Thirdspace is “a space of extraordinary openness, a place of critical exchange” and “thus the terrain for the generation of ‘counterspaces,’ spaces of resistance to the dominant order arising precisely from their subordinate, peripheral or marginalized positioning” (Soja 1996, 5; 68).

Park planners repeatedly incorporated visual traces of the ancient Maya and Aztec into the space of the park through the subject matter they chose to decorate the walls and the structures they built within it, including a large kiosko in the shape of a Maya Temple. By not only conjuring these historical moments, but actually building them into the landscape, they collapsed the theoretical boundaries between lived, perceived, and conceived space, creating their own place of resistance in Chicano Park.

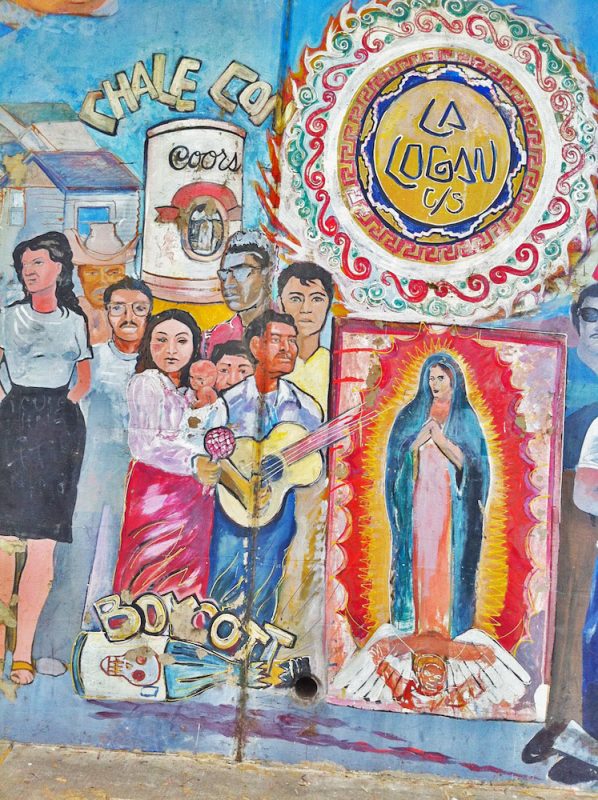

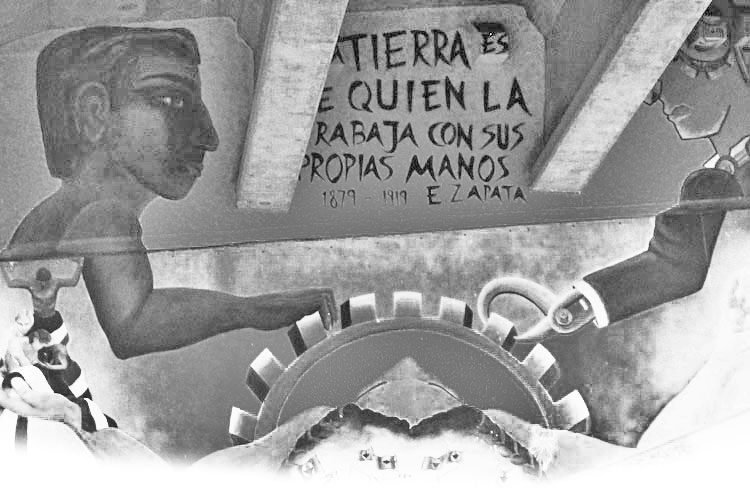

Chicano Park Murals

San Diego. Photo: Joan Saab, 2011

San Diego. Photo: Joan Saab, 2011

San Diego. Photo: Joan Saab, 2011

San Diego. Photo: Joan Saab, 2011

San Diego. Photo: Joan Saab, 2011

San Diego. Photo: Joan Saab, 2011

San Diego. Photo: Joan Saab, 2011

San Diego. Photo: Joan Saab, 2011

San Diego. Photo: Joan Saab, 2011

San Diego. Photo: Joan Saab, 2011

San Diego. Photo: Joan Saab, 2011

San Diego. Photo: Joan Saab, 2011

San Diego. Photo: Joan Saab, 2011

San Diego. Photo: Joan Saab, 2011

San Diego. Photo: Joan Saab, 2011

San Diego. Photo: Joan Saab, 2011

San Diego. Photo: Joan Saab, 2011

San Diego. Photo: Joan Saab, 2011

San Diego. Photo: Joan Saab, 2011

San Diego. Photo: Joan Saab, 2011

San Diego. Photo: Joan Saab, 2011

San Diego. Photo: Joan Saab, 2011

San Diego. Photo: Joan Saab, 2011

The kiosko, for example, is one of the only structures actually built by the people of Barrio Logan in the concrete maze of bridge and highway supports that constitutes the parkland. Conceived to resemble a Maya pyramid, it acts as both the literal and the symbolic center of the park. The covered structure is constructed out of cement, painted in bright primary colors, and open on all four sides, operating like a theater in the round. It sits directly atop one of the most symbolic sites in the 1970 takeover of the park, where a light pole erected by the California Highway Patrol stood. This light pole was commandeered early in the occupation efforts by community residents, who raised the flag of Aztlán from its height. Today, the flag of Chicano Park—which clearly delineates Chicano Park as Aztlán—is painted on pieces of mosaic in the concrete adjacent to the kiosko, thus effecting a sort of virtual time travel between the heyday of the Maya and contemporary San Diego. It spatially situates the park and its residents both inside and outside of time.

Many of the murals do this temporal work, as well. Take, for example, Toltecas en Aztlan (1973), also known as the Historical Mural. Painted on the concrete barrier abutting a freeway on-ramp, the work contains a series of portraits of well-known figures and depictions of historical vignettes from pre-colonial Mexico though the Mexican Revolution, ultimately leading up to imagery of the establishment of the park itself in April 1970. The imagery in the mural moves back and forth between the past and the present and between Mexico and the United States. Priests and priestesses dressed in elaborate headdresses and ornate jewelry are depicted alongside members of the local Barrio Logan community; men and women in professional garb, some holding instruments, implore viewers to boycott Coors beer; another group holds picks and shovels as they claim the land that would become Chicano Park. Alongside this group, a colossal Olmec head peers out at the viewer, a pair of indigenous women dressed in traditional garb wearing bandoliers brandish machine guns, and a bare-chested man rides a horse into a flaming pyre. Pyramids and mountains suggesting both the ancient Aztec and Maya civilizations fill the mural’s middle space. But the focus of the piece is the string of portraits that seem to float above the action below. According to Ochoa, the artists “thought that it was very important that our community realize that we had very important people in our history. And we did a series of portraits, to have more role models or heroes” (Robles and Griswold de Castillo n.d.).

Historical Murals

Ochoa and the other muralists involved included a variety of historical and contemporary references in their gallery of revolutionary and artistic ancestors, which contains painted likenesses of Father Hidalgo, Pancho Villa, and Emiliano Zapata, as well as Fidel Castro and Rubén Salazar. Not only are the “big three” Mexican painters (Rivera, Orozco, and Siqueiros) in attendance, but they are also joined by Frida Kahlo, Pablo O’Higgins, and Pablo Picasso. The Nicaraguan revolutionary Augusto Sandino floats between Siqueiros and Che Guevara. Next to Che is a memorial portrait of poet and activist Corky Gonzales (added, or at least edited, after his death in 2005 to include his birth and death dates and a “RIP” inscription). Shown holding a microphone, and with the black eagle of the United Farm Workers lingering behind him, Gonzales seems to introduce the largest and most central portrait in the piece: César Chávez. Below Chávez, images of pre-Columbian warriors and the iconic Virgin of Guadalupe are mixed with images of contemporary life in Southern California.

The density of references speaks to a deeply political and complexly aesthetic engagement on the part of the artists. By situating Chicano Park and its fraught creation within a broader history of colonization and coercion, the muralists place themselves and their fight for land and power within a revolutionary history and align themselves with generations of oppressed and conquered peoples across the Americas. Moreover, through references to great Mexican artists such as Kahlo, Rivera, Orozco, and Siqueiros, they legitimize their artistic practice as both muralists and activists. These nods to Mexican artists in this and other works in Chicano Park contain multiple levels of citation. They pay homage to the artists themselves while also evoking the subjects and scale—as well as the process and politics—of these earlier public art works (many of which also celebrated pre-conquest Maya and Aztec civilizations as a means of visually encouraging pride and resistance in the wake of the Mexican Revolution). Further, by including Picasso as an artistic forbearer, the muralists in Chicano Park place themselves within the legacy of an international modernism that includes but is not limited to Mexican muralism.

The artists who painted the walls of Chicano Park have created a visual canon of Chicano art. Each image contains a potentially larger history, one that reaches back before 1492, through the monumental work of the early 20th century, and into the present moment. To make this history clear, park muralists painted multiple vignettes that relate the space of Chicano Park to Chicano art history. Through multiple levels of citation, the variety of artworks in the space reference many sites and strategies of resistance, as well as the media that enabled these acts of confrontation over time: indigenous warriors wield machine guns in much the same way that the artists of the Mexican Revolution employed fresco and that contemporary activists such as Gonzales and Chávez hold microphones to disseminate their messages of unity and resistance. The residents of Barrio Logan, meanwhile, use picks, shovels, and musical instruments. And, of course, the muralists who painted this and the adjacent walls deployed cans of spray paint and muriatic acid to spread their own stories and methods of resistance.

Chicano Park

Today, the visual history of Chicano Park and its legacy of resistance has transcended the space of the park through new and accessible forms of vernacular media: flip cameras, cell phones, and websites. Type in “Chicano Park” on YouTube, and links to a number of homemade videos appear. Many of them are set to “Chicano Park Samba,” and all of the ones I looked at feature some assortment of the park’s colorful murals. The terms of creation and production values for these works vary. Reading the comments that accompany each video often helps to situate its individual history of production: some had their genesis as school assignments and have voiceover and more didactic history lessons embedded in them. Others function as diary entries marking a trip to San Diego or a special event, such as a wedding or the annual Chicano Park celebration. Others are works of homage, a means of paying respect to the site and the multiple histories contained within it.

Despite their differences, all of these short videos are now part of the palimpsestic history of the park. They circulate the experience of the space to viewers who may not be able to visit San Diego while communicating with those who know and love the site. They simultaneously reaffirm the familiar narrative—“in the year 1970, in the City of San Diego…”—as they pass on its history and legacy to a new generation of artists and activists. Through their homemade montages, these videographers take ownership of the space and the stories associated with it. In each case, the often-anonymous filmmakers join the cast of historical actors—from the ancient Maya to the residents of Barrio Logan—both on display in and creating work about Chicano Park.

By placing their filmic narratives in digital space, these vernacular videographers further complicate our notions of space and time. They take images that are site-specific and fixed in concrete and allow them to move. Through these moving images they simulate the experience of seeing the site and its murals from a passing vehicle, thus transferring the ephemeral experience of seeing the works in real time and space to each viewing. But on YouTube, we can hit pause and zoom in on a particular frame or rewind back to catch a detail that we may have overlooked at first. Unlike drive-by or walk-through experiences of Chicano Park, in these video incarnations of the spatial experience, the spectator stays still while the images move in front of them. The history of Chicano Park—and its multiple sites of citation and resistance from the 1840s to the current day—becomes animated over and over again as the story moves across the screen. In their moving form, these videos are able to keep the history active and tell the story of that little piece of land under the Coronado Bridge to new audiences in spaces across the digital universe.

Works Cited

Anaya, Rudolfo. 1989. “Aztlán: A Homeland Without Boundaries.” In Aztlán. Essays on the Chicano Homeland, edited by Rudolfo Anaya and Francisco A. Lomelí. 230-41. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press.

Anguiano, Marco. N.d. “The Battle of Chicano Park: A Brief History of the Takeover.” Accessed 1 June 2016. http://www.chicano-park.com/cpscbattleof.html

Cockcroft, Eva. 1984. “The Story of Chicano Park.” In Aztlán: International Journal of Chicano Studies Research 15.1: 79-103.

Robles, Kathleen and Richard Griswold de Castillo. N.d. “Historical Mural.” Accessed 1 June 2016. http://www.chicanoparksandiego.com/murals/history.html

Rosen, Martin D. and James Fisher. 2001. “Chicano Park and the Chicano Park Murals: Barrio Logan, City of San Diego, California.” The Public Historian 23.4: 91-111.

Soja, Edward. 2010. “Soja: Third space – Alternative way for looking at space.” Accessed 1 June 2016. https://vimeo.com/15947625

Soja, Edward. 1996. Thirdspace: Journeys to Los Angeles and Other Real-and-Imagined Places. Cambridge, MA: Blackwell.