Spanning over 5 years of Moysés Zúñiga’s work, Lost and Found chronicles the perilous sojourn of Central American migrants across Mexico’s southern border and northward, through Mexico, towards the United States. In Zúñiga’s photographs, we find the countless faces and lives made invisible by the criminal and structural violence that expels hundreds of thousands from their communities, and thrusts them into states of radical vulnerability as they travel along migratory routes. With his photographs and detailed firsthand accounts, Zúñiga immerses the viewer in rare and specific glimpses of narratives from Mexico’s southern border—stories that are virtually ignored by mainstream media in the United States. Migrants are besieged by petty thieves, criminal gangs, corrupt public officials, unscrupulous businessmen, and an indifferent public opinion. Each photograph at once suspends and condenses the terror and defenselessness that mark the movement of migrants—on foot, by bus, on rafts, by train—through a succession of predetermined landscapes, each harboring its own risks and predators. The fleeting reassurance of having reached each destination along the route only implies the dangers that lay ahead. Each leg of the journey marks another repetition of the endless cycle that migrants face—robbery, extortion, mutilation, torture, rape, sexual servitude, amputation, and disappearance. Some are apprehended early on by Mexican immigration authorities and deported back to their countries of origin, only to attempt the crossing again. Some fall off of La bestia (“The Beast”), the infamous migrant train, or are kidnapped by criminal gangs and never heard from again. Women and girls are particularly vulnerable, with many coerced into sexual slavery in the cantinas and dance halls that line the streets of border cities like Tapachula. Countless others abandon the journey altogether and settle in Mexico under a punishing regime of illegality. In Moysés Zúñiga’s photographs, those lost in this machine of suffering and death are found, alive and in full possession of their humanity.

San Cristóbal Verapaz, Alta Verapaz, Guatemala. 29 February 2009.

“GO” Find other pathways, outside of your homeland, other realities, other gazes, ones that are less painful with a little bit of hope and far away from your family.

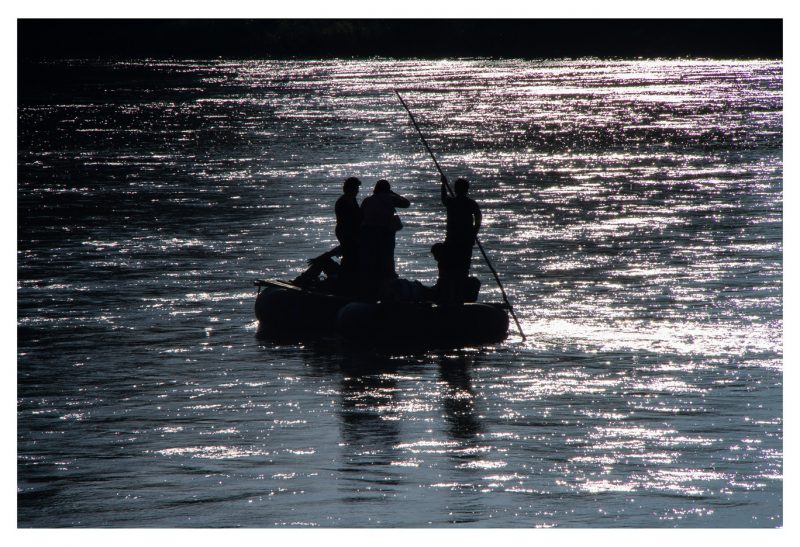

Rio Suchiate, Ciudad Hidalgo, Chiapas. 5 May 2014.

The Suchiate River is the natural and political border between Mexico and Guatemala. The river is shallow, only 5 feet deep in its most profound parts, and thus easy to cross on rafts made out of used tires and wood. Balseros (rafters) charge $1.50 USD for crossing, and half in times of drought. Children, women, and families cross every day. Buyers and sellers of basic products, both from Guatemala and Mexico, meet in the site and trade, taking advantage of the low process of goods in supermarkets. The rafts are also used for trafficking weapons, drugs, and people. Some of those who cross will return to Guatemala that same afternoon, others will stay and work in the first Mexican city they reach. The vast majority however, have the United States as a final destination, and Mexico is just an in-between territory that needs to be crossed.

name and date

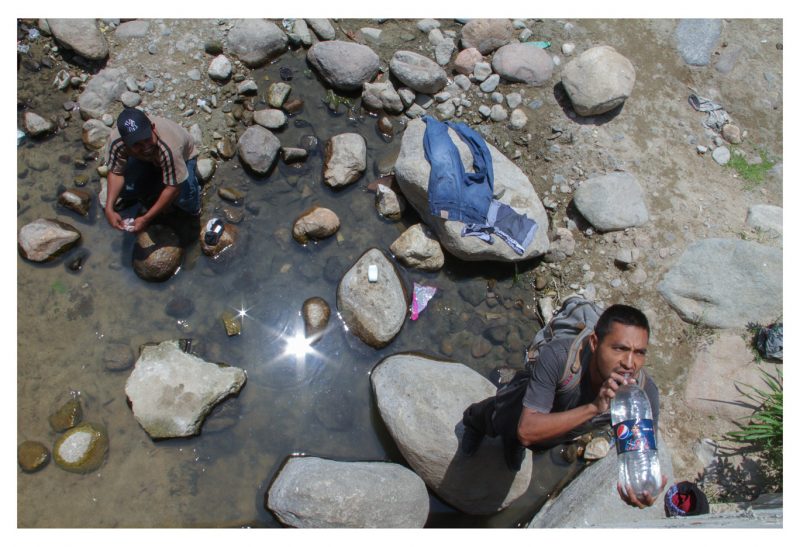

Arriaga, Chiapas. 19 April 2012.

After traveling nearly 200 miles in buses and hidden inside cargo trucks from Mexico’s southern border to Arriaga, in Chiapas, thousands of migrants from Honduras, El Salvador, Nicaragua, and Guatemala take a break for the first time. They wait for the cargo train that crosses Mexico through the Gulf route, infamously nicknamed “La Bestia” (The Beast). This route is one of the most dangerous of the country due to the high number of kidnappings and thefts perpetrated by groups of organized crime.

Tapachula, Chiapas. 31 July 2014.

Undocumented immigrants, in the hope of legalizing their migratory situation, survive on others’ waste. 80 families from Guatemala have been living in the municipal dump of Tapachula, Chiapas for two years. In this settlement, known as Linda Vista, 220 children have been born, they are Mexican by birth.

Inhabitants of Linda Vista are paid $3 USD per day for collecting trash. Recycling companies offer $0.02 USD for a pound of cardboard, $0.05 USD for a pound of metal, and around $0.08 USD for a pound of plastic. A space for sleeping is $3.50 USD a week. Needless to say that living conditions are inhumane.

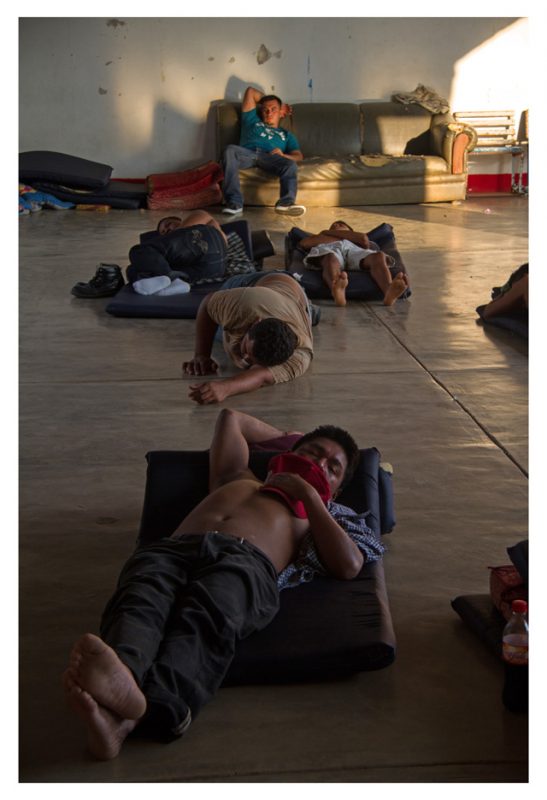

Arriaga, Chiapas. 6 May 2014.

Some young men and Roberto, age 12, ask for help from drivers alongside the train tracks in Arriaga, Chiapas. Bus passengers and car drivers watch the migrants searching for food under the sun and sometimes hand them some change, food, and clothes.

Arriaga, Chiapas. 6 May 2014.

A 23-year-old Guatemalan closes the visitor gates of the “House of Mercy,” a shelter for migrants in transit run by the Catholic church. On average, 80 people per day stop by the shelter to get food and rest as they wait for the train, that passes every two or three days. The shelter, surrounded by metal bars and armed police officers, is constantly under the threat of organized crime groups and trafficking gangs.

Arriaga, Chiapas. 6 May 2014.

Immigrant women and girls face an extra set of challenges; in addition to the physical barrier established by the Soconusco River in Chiapas, they encounter discrimination, and have to constantly fight abuse and stigma. In the south of Mexico, the destiny of women is often determined by their country of origin. Guatemalan women are thought to be limited to housework. Honduran women, on the other hand, are enslaved in bars or canteens; women from El Salvador are plain invisible. Along the border, women are not more than what their countries of origin—and society—have condemned them to be.

Arriaga, Chiapas. 6 May 2014.

While riding the train, a Honduran child turns her gaze at me as she gets her hair done. She is from San Pedro Sula, the most violent city in the world, where hope is non-existent and death, confused with dust, seizes the souls of “guiros”, as kids are called in Honduras. Faced with the choice of either becoming paid assassins for local gangs, or killed because of refusing to do so, children flee their country. Sending an unaccompanied child from Honduras to the border of the United States can cost up to $5,000 USD. This cost includes travelling in luxury buses through Mexico, and the payments made to cartels and Mexican authorities in order to cross the country without risking detention.

Arriaga, Chiapas. 20 July 2014.

The Mexican economy is highly dependent on the more than 400,000 people who cross the border to the United States every year. This million-dollar economy is reliant on immigrants; be it by selling cardboard and plastic, renting spaces for spending the night, paying for buses to move through the country, and sending remittances through places like Western Union, the migrants are seen as a continuous source of income. Organized crime groups also profit extensively from the migrants’ vulnerable conditions.

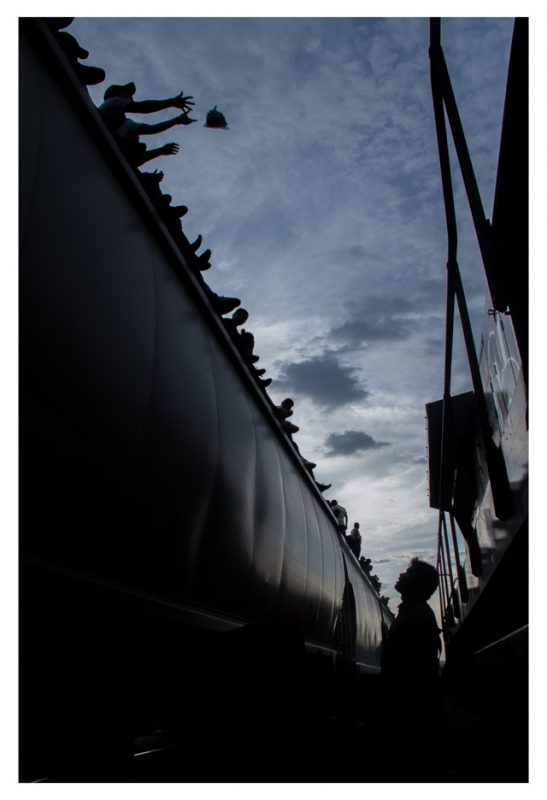

Border Between Chiapas and Oaxaca. 16 May 2012.

The cargo train, with hundreds of migrants on board, crosses a bridge known as the bridge of the bees because of the frequent attacks of bees due to the vibrations caused by the train’s passing. The 200-mile train ride lasts for more than 14 hours, where passengers have to cope with temperatures of more than 100 degrees (F), dehydration, and starvation. In a car, the same distance takes only 3.5 hours.

Arriaga, Chiapas. 29 July 2014.

The unceasing dangers that the train ride entails soon reveal that the American Dream is more like a nightmare. Life can change from one moment to the next; migrants are in constant risk of falling from the train and getting run over as well as of being robbed and kidnapped by organized crime groups.

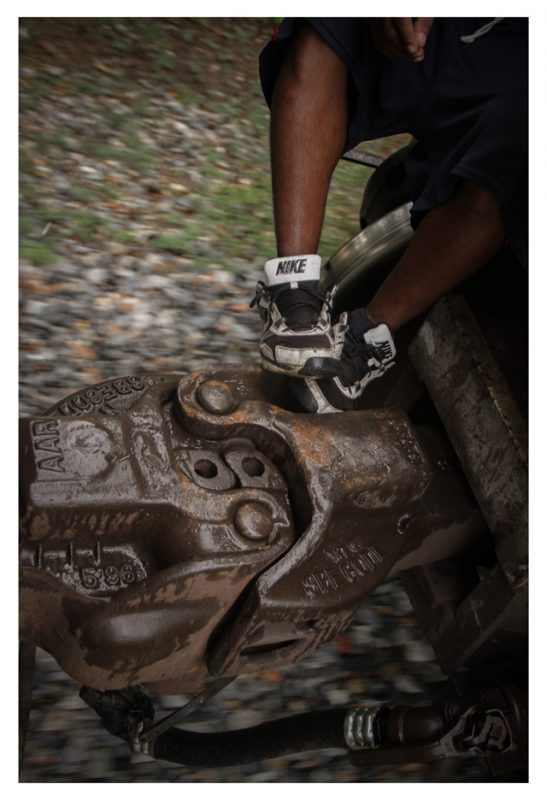

15 May 2012. It was José Luis’ second try to cross the U.S. border. He and his friend Selvi took 19 days to get to from Progreso, in Honduras, to the north of Mexico. They boarded the train in Tapachula, Chiapas and got off in Chihuahua, in order to cross the border in Ciudad Juárez towards El Paso, TX. José Luis’ main task throughout the journey was to keep Selvi from falling asleep. He kicked and pestered his friend until he got angry, all in order to keep him awake, and alive. José Luis, a talented soccer player, guitarist, and amateur fisherman from the Ulúa River, was riding close to the couplings between train cars and leaned forward to tie his shoelace. He had never been in the desert before, and his face was covered in sweat. The train entered a town called Delicias and José Luis nodded off. “Suddenly all turned dark and I fell. I passed out due to the heat, that dry heat of June in the Mexican desert. The train chopped off one of my legs. I tried pulling my leg out with my arm, and lost it as well. I tried using my other arm but the train wheels ran over it.” Selvi did not notice what was going on until, miles later, he saw the train wheels covered in blood. He assumed his friend was dead. Selvi now lives in the United States where he has a family. South of the United States, his friend who kept him from falling asleep in the train, struggles for balance as he walks on the one leg that La Bestia spared him. —Rodrigo Soberanes, Red de Periodistas de a Pie

Chahuites, Oaxaca, México. 16 May 2013.

Once upon a time there was a country where those escaping dictatorships and violence found a home. It was a place where the exiles were fed, and granted citizenship by the government; a nation that promoted peace among its Central American neighbors and defended the right to be neutral in a world plagued by war. But that paradise was lost and is now more frequently compared with hell. That country is Mexico, one of the largest migrant graveyards in the world. —Alberto Najar, Red de Periodistas de a Pie

México, D.F.. 11 April 2014.

José Luis puts on his prosthetic leg, wears his one-sleeved shirt, and wraps a handkerchief around the only finger that he has left after that day in the Mexican desert when he fell off of La Bestia. After being in the city for several years, he is now well known. He was first acknowledged for his talent for singing religious songs and rancheras. 8 years ago he began being recognized as the man who lost an arm, a leg, and four fingers when he fell off La Bestia on his way to the United States. He was traveling without papers on his second attempt to cross the border. He is now the president of the Organization for Returning Immigrants with Disabilities, which calls for an end to the state-sanctioned persecution and violence that forces people to board the train and risk their lives.

Arriaga, Chiapas. 29 July 2014.

A peddler throws a fruit bundle over the train before starting his 14-hour travel towards Ixtepec, in the State of Oaxaca.

Arriaga, Chiapas. 6 May 2014.

Rest is essential after travelling the 200 miles that separate Mexico’s southern border from Arriaga, in Chiapas. Some travellers lay down to feel the warmth train’s roof on their backs and are able to close their eyes and dream. What do you dream about with all those yearnings and a past that turns blurry as days go by? Migrants dream of their homeland, to keep memories from fading away. They wish to imagine those moments spent with their family that will not be possible again. They dream about the past and the future they long for; the present is just insomnia.

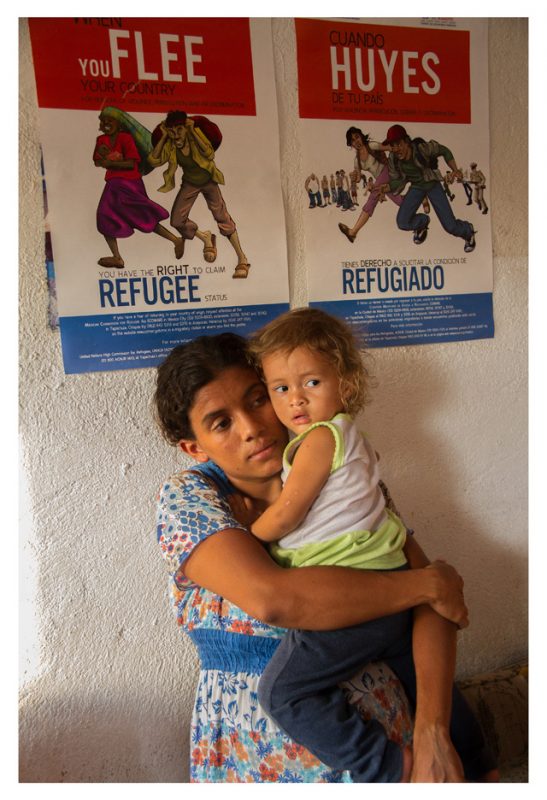

Arriaga, Chiapas. 6 May 2014.

Esther, from Honduras, is seven months pregnant and has a two-year-old daughter. She has only made it as far as Chiapas and has already been robbed—everything, even her clothes stolen. All she has left are her daughter’s garments. Their future is uncertain, as she has neither family in the United States waiting for her, nor family in Honduras that supports her in order to make the trip possible. She does not want to get on the train, so she stays in the shelter in Arriaga waiting for some resolution.

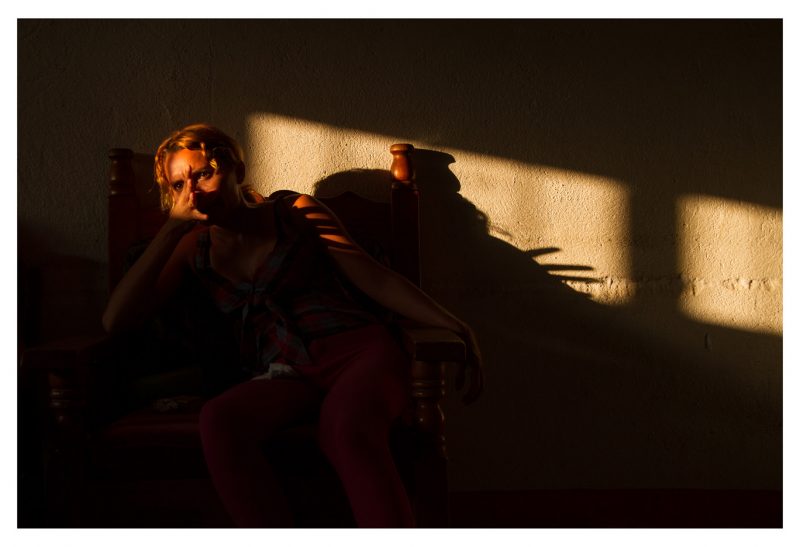

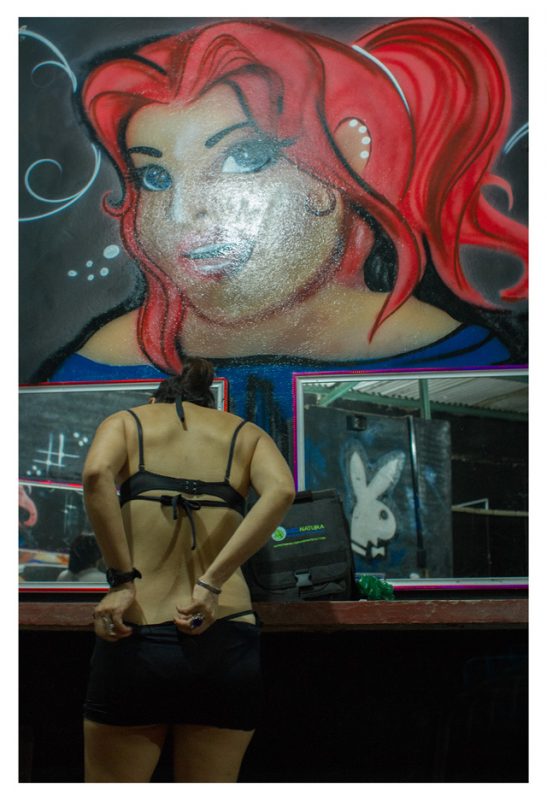

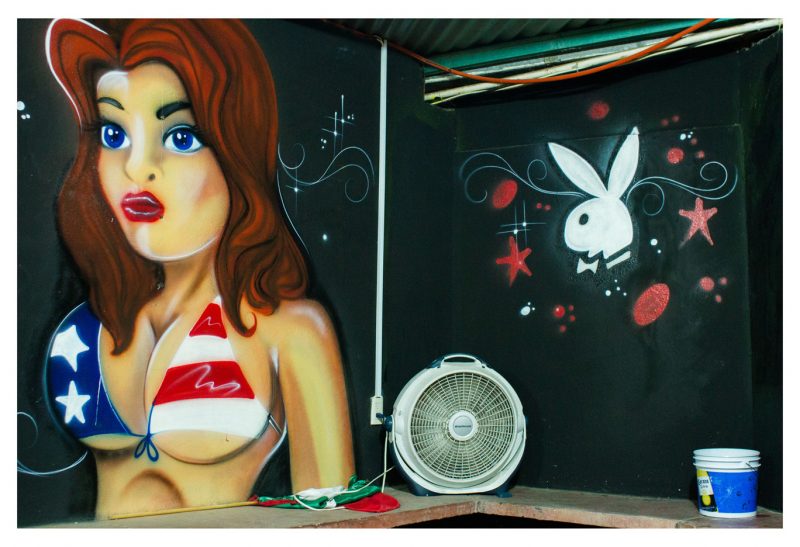

Tapachula, Chiapas. 5 May 2014.

Accordions, trumpets, and bongo as background music. The body of the dancer flexes on stage as she strips to the rhythm of a cumbia. The owner of the place, a 50-year-old woman from the south of Mexico, agrees to show us around and take us backstage to introduce us to the dancers. She insists there is no sex work going on in this establishment. “The only thing we sell here are fantasies,” she says. “Most guys just want to see them strip, dance with them, and chat with the catrachas (Hondurans) who are believed to be the most beautiful. We also have dancers from Guatemala, El Salvador, and Nicaragua. “There are other places for sex,” she insists. Inside the dressing rooms, the fantasy sold outside crumbles. The woman in this photo is 23 and has three kids. She says she had to leave her country in 2009, because of trouble with her past partner. “He joined the Maras and as you know, my country is very violent…I had to get out.”

Melani left her kids with her mother for a while, and brought them with her once she settled in Tapachula. “He hits me because he is jealous. He says the clients stare at me (he worked for a while as a bartender in the same nightclub). But this is how I pay my bills and support him as well. What does he want, for me to work at a store counter? We don’t get hired there because they say we are thieves, and even if we do get a job we are paid nearly nothing. I already told him, you decided to be with me, a Honduran, and this is what life is like for us. This is the only place where they treat us and pay us well.” Melani has to deal with the stigma of being a catracha everyday. Being a catracha means being considered an “expert lover.” Her body betrays her, her wide hips, long legs, and slender waist don’t allow her to go unnoticed. “If I get in a cab, the driver wants to grab my legs; if I work at a store, my boss will want to mess with me,” she complains.

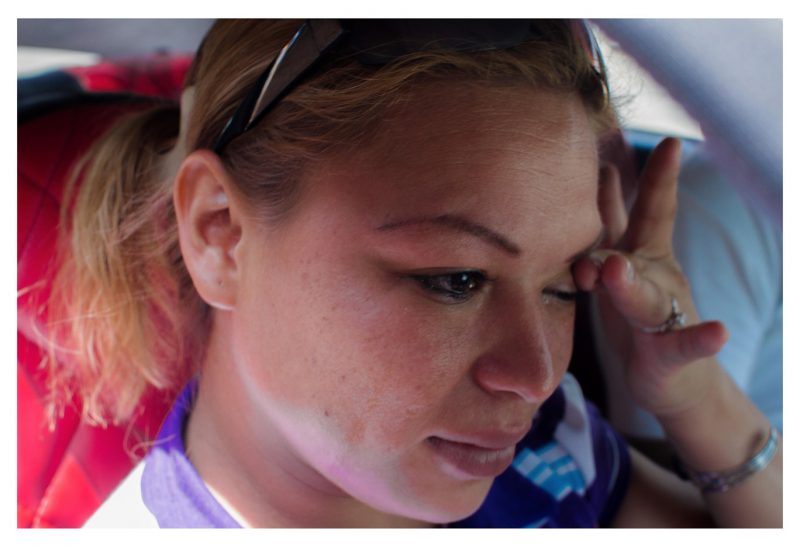

Tapachula, Chiapas. 6 May 2014.

The young Honduran woman leaves the office carrying an order of deportation in her hands. Ten years of living in Mexico, with children born there and a Mexican partner, were not enough evidence for the authorities of the National Migration Institute (Instituto Nacional de Migración) to grant her legal recognition to stay in Mexico. The only thing she regrets, she says as she slams the door of the office in Tapachula, is the fact that she was hopeful until the end of the six month bureaucratic process. It all started with her application, and involved her both going to the office every week to follow up until this day as well as spending close to $400 USD just for the application procedures. “I want to solve my situation, get my papers in order. Even though I did not have enough money to pay for it, I was told I had to do it so I did. Now they just tell me ‘no, you have to leave the country.” She feels “illegal,” criminalized, and vulnerable in a country that offers her a supposedly legal stay while at the same time aims to kick her out. Her name is now in the system with other more than 2,476,000 people who have applied to regularize their migratory status from November 2012–October 2013. Now, even the hope of one day being able to walk safely and freely through the streets has been taken from her. If she uses regular transport she risks being identified as an immigrant and being deported. She cannot apply for formal employment, not even at a drugstore, since she does not have a current passport or the migratory form needed for formal employment (FM2). “They won’t take you.” She cannot open a bank account to purchase a house or room. She will live in constant fear and uncertainty, and with the ever-present threat of expulsion from Mexico. Nevertheless, she gets in a taxi and guarantees that the recent denial for legalization will not hinder her search for safer and better conditions in Mexico City.

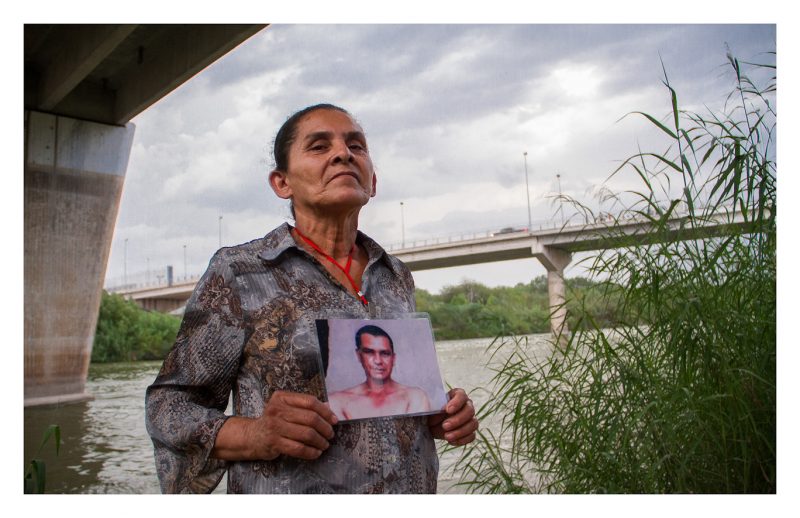

Reynosa, Tamaulipas. 18 October 2012.

Standing by the sandy edge of the Río Bravo, the physical and political boundary between Mexico and the United States, Socorro García takes a picture of herself. She is looking for one of her 11 sons, Jesús de La Concepción García, from Nicaragua. She is part of “Liberando la Esperanza,” a caravan composed by family members of migrants who have disappeared while crossing Mexico that is coordinated by the Mesoamerican Mexican Movement (Movimiento Migrante Mesoamericano).

Tequisquiapan, Estado de México. 24 October 2012.

Ángel holds a bar of soap while he waits for his turn to shower in one of the major shelters near Mexico City, the country’s capital. Shelters in the region have been shut down due to confrontations between organized crime groups who fight for the control of Central American migrant transportation routes through Mexico.

Tequisquiapan, Estado de México. 24 October 2012.

A mother of two disappeared Central American immigrants prays to find her children. Two years later, they were able to reunite.

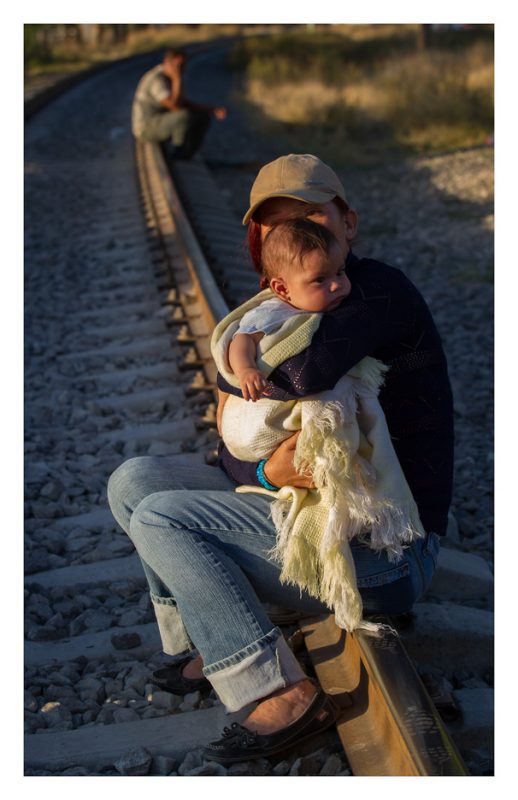

Reynosa, Tamaulipas. 23 October 2012. A woman waits for the train by the tracks. The train will get her to the Mexican border with the United States. Around here there are no big groups of immigrants, the only ones left are those who managed to survive all the way from the southern border.

Tequisquiapan, estado de México. 26 October 2012. Sheyla, only accompanied by her newborn son, waits for the train that will take them to the northern border of Mexico.

23 October 2012. An “anonymous” migrant man, who I followed from Veracruz until Nuevo Laredo, sits on board of the cargo train. He was kidnapped and his companions murdered by gangsters. Extortion, rape, mutilations, and the constant risk of being handed to criminals by Mexican authorities permeate the immigrant experience through Mexico. Looking firmly at me he said: “I don’t want to continue, but it’s equally risky to continue than to go back…if I go back someone could kill me. I am trapped here and I don’t know what to do.”